New venture capital structures in crypto markets

TL;DR

In this article we will examine the state and structure of venture capital financing in crypto markets. We will then suggest alternative structures that we think will lead to better long-term incentive alignment between founders and investors. Specifically, we will attempt to answer the following:

How can liquidation preferences be represented in tokenized fundraising models?

Can liquidation preferences be truly represented on-chain without fully gating the proceeds from the “sale” / liquidity event of a project?

Can participating liquidation preferences be modeled as a two-part token representing the “common” token and the “liquidation preference” token?

Background, motivation, and vision

Blockchain technology companies attracted over $35bn venture capital financing in 2021. Despite the fact that there is a growing amount of interest to finance the future of decentralized technologies, private market financing structures have not evolved to provide investors with the flexibility and protections that are typically afforded in traditional venture capital financing. Here we survey the current (and suggest new) deal structures in venture capital financing that will unlock more capital by protecting the interests of the investors as well as aligning incentives between founders and investors.

The following discussion is motivated by the current state of venture capital financing and tokenomics design in the crypto market. There are many potential avenues for improvement. Not only can one improve tokenomics design to ameliorate shortcomings in venture capital financing in crypto, cryptography and public ledgers can themselves revolutionize the structure of traditional venture capital.

We hope that this is the first of many works addressing the use of cryptographic primitives in venture capital financing in order to bring transparency, accountability, cost reduction, uniformity, accessibility, and ultimately aid fiduciaries in fulfilling their duties as operators and stewards of capital.

Traditional venture capital financing structure

The most prevalent mechanism in traditional venture capital financing is the issuance of Preferred Shares to investors. Preferred Shares can have a variety of attributes, but out of them all the most critical feature is the liquidation preference. In its most basic definition, without delving into the nuances of participation / non-participation (a term that characterizes how the liquidation preference will be executed in the liquidation waterfall), liquidation preference gives the investors the option to receive their principal investment or receive proceeds with the founders as common stockholders.

Common stockholders (usually, the founding team) have to create an exit outcome for the company leading to a windfall that is greater than the amount of money they raised in the form of Preferred Shares before having any value accrue towards their common shares. This achieves two critical goals: (1) investors have some downside protection, as even in the case of modest exits, their Preferred Shares enable them to recoup all or some of their principal back (2) the teams need to create more value in terms of exit proceeds than the amount they raised in order to realize any proceeds, which disincentivizes them from making decisions that do not align with the long term growth and sustainability of the enterprise.

The Preferred Stock mechanism works well in traditional venture capital as the company shares, both common and preferred, are illiquid (in most cases). Since the team cannot generally extract value by selling their shares, their main goal becomes creating a company that, in a liquidity event, is more valuable than the amount of cash invested such that the common stock has value. In crypto markets, the premature liquidity of tokens violate the aforementioned premise, thus making it difficult to have a simple preference stack, and thus maintaining investor downside protection and long-term incentive alignment. Moreover, unlike in traditional venture financing, most crypto enterprises have no valuable intellectual property (it is mostly open source code), thus making traditional liquidation (in case of winding down) problematic, as the residual value in the event of a wind down is minimal.

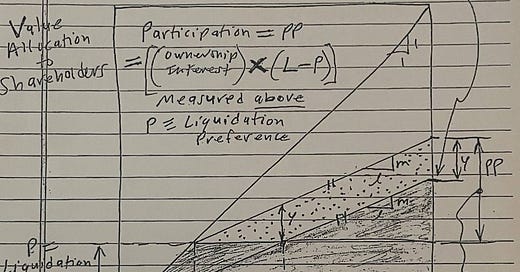

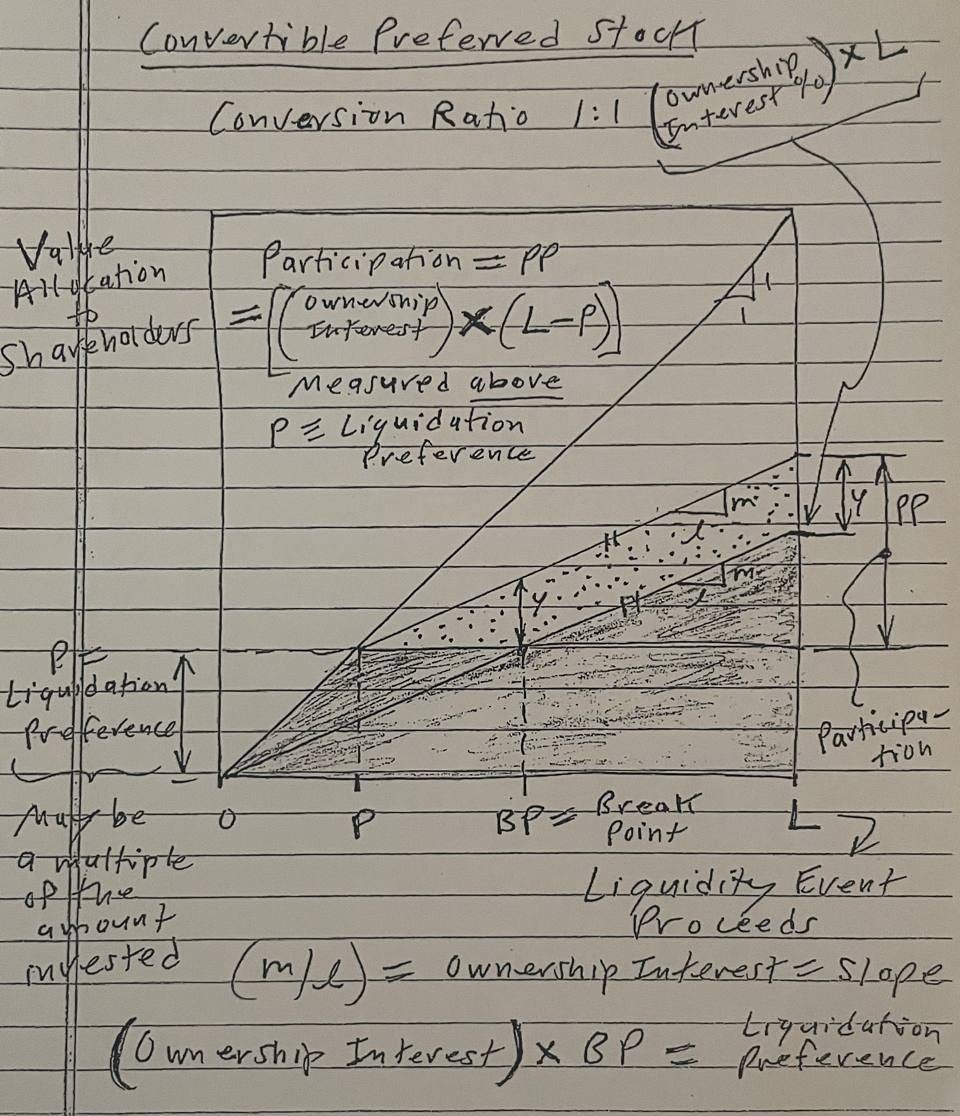

Figure 1. Payoff Diagram: Convertible Preferred Shares. This diagram illustrates the threshold levels (of liquidity events) at which proceeds are distributed to shareholders. Figure courtesy of Akash Nath (X3E Capital).

Current venture capital financing structure in crypto markets

In crypto market financing, token vesting schedules have arisen as a replacement for the traditional preference stack. Tokenomics usually have shorter lock-up periods and / or faster vesting schedules for the investors relative to the founders in order to mimic the preference of the shares (tokens) that an investor holds. This method appears to work initially, but upon closer inspection its shortcomings become clear. Once the vesting periods for the investors and founders conclude, the investors have no further downside protection. This structure may incentivize the founders to focus on the short term by shifting their focus towards creating fleeting value, up until their tokens are fully vested. Furthermore, it can incentivize inefficient capital expenditure as founders are incentivized to optimize for creating the largest possible market capitalization by the end of their vesting period, rather than to aim for sustainable long term value creation. Moreover, owing to the current regulatory circumstances, secondary liquidity is easily obtained (e.g. DEX listing), which may lead to perverse incentives for both founders and investors.

KPI-based vesting

As one of many possible solutions, we first consider KPI-based vesting. This method focuses on creating goal-based, dynamic vesting structures. A smart contract can be written to adjust vesting parameters based on an on-chain verifiable KPI, such as protocol revenue (its origin may be exactly enshrined in the smart contract). The investors and the team can agree on vesting parameters and revenue expectations when financing occurs, and accountability and transparency preside over the token distribution process.

KPI-based vesting is a step improvement over current vesting models. Although it still does not create a true liquidation preference for the preferred shares (investor tokens), it can be used to calibrate vesting periods of common shares (team tokens). If the project is reaching their KPI goals, which should translate to value creation with the appropriate KPI selection and token value accrual design, the team can vest their tokens faster, as liquidation preference of preferred shares become of secondary importance. Conversely, if the project is falling behind their KPI goals, team vesting slows down to prolong the time between preferred share (token) liquidity and common share (token) liquidity, mimicking a liquidation preference given to the preferred holders of tokens. Needless to say, the above two outcomes lie on a spectrum and can be as close or as far from each other depending on the parameter selection of the structure.

Key parameters

Total tokens for the team to vest (“Tokens”)

Lock-up period (“Lock-up Period”)

Vesting Period (“Vesting Period”)

The KPI: e.g. Expected Revenue per month during the Vesting Period (“Expected Revenue”) and its exact origin (enshrined)

A multiplier to determine the maximum acceleration of the vesting period due to overperformance (“Maximum Vesting Multiplier”)

A multiplier to determine the maximum deceleration of the vesting period due to underperformance (“Minimum Vesting Multiplier”)

Let us demonstrate with an example:

Team XYZ has 24,000 Tokens to vest after a lock-up of 1 year (Lock-up Period) and vesting in 2 years (Vesting Period)

From Month 13 – 36, they should vest 1,000 tokens every month for the base case, based on an expected monthly revenue of $100,000 (Expected Revenue)

Let’s work with a Maximum Vesting Multiplier of 2 and Minimum Vesting Multiplier of 0.5

Execution of the vesting calculation can be done in a variety of ways, but for simplicity let us use linear form:

If Revenue < Expected Revenue

Max (0.5, 1 + (Revenue - Expected Revenue) / Expected Revenue)

If Revenue ≥ Expected Revenue

Min (2, 1 + (Revenue - Expected revenue) / Expected Revenue)

The vesting continues until the team fully vests their token allocation. There are further nuances that can be added to the KPI-based vesting structure such as variable KPI parameters to factor in protocol growth, multiple scenario outcomes, and so on. Of course, cryptographic schemes allow for these structures to be modified (perhaps automatically) in real time, thus giving further flexibility. We note that the KPIs have to be robust enough to prevent manipulation by any party (e.g. by enforcing that the debt has to be paid off from a pre-deployed contract that can only receive funds from fee pool, monitoring revenues relative to token emissions, etc). Investors can have multi-sig access in case this needs to be modified in the future in the case of an exploit, bug, discretionary, and so on.

Strengths

Treats founders fairly by opening the doors to accelerated vesting in projects with success.

Aligns the team better with the investors by incentivizing them to focus on sustainable value creation.

The on-chain transparency allows retail investors to assess the quality of potential projects and the viability of their roadmaps (since they are constrained by the KPIs).

Weaknesses

It’s not an exact representation of the traditional preferred shares because all liquidation preferences are removed after all parties fully vest.

Needs an objective and on-chain verifiable KPI metric to work, which may be subject to manipulation, and a robust token model design.

General vesting restrictions complement liquidation preferences. Other approaches can include transfer restrictions (inhibits secondary market liquidity pre-liquidation event) or restrictions on distributions from the treasury that require preferred token holder consent (limits ability to pull money out of the project through, e.g., extraordinary bonuses or paying for household expenses). These are codified checks on potential founder abuse, e.g. preventing the founder from prematurely extracting value from the business through improper back doors.

Community distribution: Retroactive airdrops

We now slightly digress to consider the case of “community airdrops”. In an attempt to incentivize certain behavior (typically liquidity provision), most protocols use some form of airdrops. Here we argue that upfront airdrops, where upon performing the action required the agent immediately (or almost immediately) receives a token reward, are both futile and unnecessary (e.g. see the case of the Uniswap airdrop). Instead, the retroactive KPI-based airdrops are likely to provide better token distribution and achieve long-term incentive alignment between token holders and the protocol. We note that since retroactive airdrops can be priced similar to exotic options, a KPI-based retroactive airdrop can allow for a more precise cost-benefit analysis ex ante and enable fine-turning of the airdrop campaign.

We proceed with an example. Instead of asking users to provide liquidity into a pool now (provide liquidity now) and receive immediate rewards (farm and dump), the user will instead receive an airdrop based on their historical liquidity provision profile (a distribution, as opposed to a point in time). Then, one can have a coherent measure of “contribution” to the protocol, and reward users accordingly. More importantly, this has a natural anti-Sybil mechanism. While it is easy to Sybil attack a protocol that uses time snapshots based on participation (as opposed to contribution), it is difficult to do so when using historical profiles since the contribution measure scales with, say, size of liquidity, as opposed to the number of accounts that provide liquidity or just the unconditioned absolute amount of liquidity provided.

We reiterate that the point of an airdrop is to incentivize users to perform certain actions that they would not otherwise carry out in the absence of intrinsic economic reward. For example, fleeting liquidity (or narrow liquidity in general) can avoid toxic flow by providing liquidity only near the mark and withdrawing it during times of volatility. However, in the early history of a pool, liquidity is needed across a large band around the mark (say ±5%, which would make the liquidity provider susceptible to toxic order flow). However, the airdrop is to act as a protection against excessive toxic order flow, in so much as the liquidity contribution ends up causing net benefit for the protocol, thus ultimately leading to the prosperity of the protocol (and presumably token price appreciation). It is apparent that while immediate liquidity rewards incentivize immediate liquidity, appropriate KPI-based airdrops can incentivize long-term liquidity and mitigate excessive loss due to toxic order flow.

The problem then becomes defining: (1) the measures / KPIs used for the airdrop so that it may be priced; and (2) a proper token model so that the success of the protocol (say, larger liquidity over time) eventually is reflected in the price of the token, so as to be indeed beneficial to the airdrop recipient. A simple example of a measure would be that of uniform liquidity provision (Uniswap v2 style), where the airdrop would be proportional to some function h(a, b, t) such that a represents the nominal liquidity, b represents the efficacy of liquidity (percentile, conditioning on volatility, etc), and t represents total elapsed time / trade frequency of liquidity provision. One would expect b to be inversely proportional to impermanent loss.

Founder bootstrapping on-chain

Here we consider a variant of founder bootstrapping for a crypto startup. Using concepts such as dID, soul-bound tokens (SBT), and the immutability of distributed ledgers. We posit that founder bootstrapping can both increase the accountability and transparency of venture financing.

Income sharing agreements (ISAs) are gaining some traction as a primitive for founder bootstrapping, where the founder effectively incurs debt to be paid off from future revenue. In this case, the founders themselves would be personally liable (from their future income) to pay their investors back in the event of default. ISAs are being positioned as alternatives to traditional loans for educational expenses, amongst other uses. Using privacy technology, we can imagine a future in which the founder is liable for some portion of the funds raised without revealing the exact nature and details to the public (so as to preserve privacy while maintaining Sybil resistance). However, coupled with an appropriate verifier-prover system, an SBT can be used as a primitive for founder bootstrapping.

On privacy, it is important to distinguish between founder and user anonymity. A founder who raises capital is a steward of capital and carries a fiduciary duty to their investors, and accountability is most easily assured through transparency. Users, on the other hand, pay for a service there and then, and no financial responsibility exists between the founder and user after the transaction.

Strengths

Increases the accountability of the founders to protect investors money. Skin in the game.

Weaknesses

Increases the barrier of entry for being an entrepreneur.

Non-transferable token for protocol proceeds

This method utilizes a smart contract that can distribute the proceeds from a protocol based on the preference class of the investors. Different classes of profit participation tokens can be created as non-transferable tokens entitle the wallets that hold them to receive protocol proceeds, according to the preference stack. This method requires segregated profit participation tokens, a protocol token, as well as a mechanic to capture at least some of the protocol value creation.

Let’s use an example to demonstrate:

Project xyz has its own utility token XYZ.

The project raises first $1M @ $10M (10%) post-money valuation from its Series Seed investors and then $5M @ $100M (5%) post-money valuation from its Series A investors.

Series A investors have preference over Series Seed investors, who have preference over the Team Stake.

pXYZ is a token that represents profit rights to the protocol proceeds and has the below classes

pXYZ-A representing the proceed rights of Series A investors,

pXYZ-S representing the proceed rights of Series Seed investors,

pXYZ-T representing the proceed rights of the Team.

The protocol has a value capture mechanism for the use of its XYZ utility token that accrues value towards a profit distribution pool (“PDP”).

The first $5M that is captured in the PDP is distributed on a pro-rata basis to the pXYZ-A holders.

The next $1M that is captured in the PDP is distributed on a pro-rata basis to the pXYZ-S holders.

At this point, the liquidation preference of the investors are met and the non-transferable pXYZ-A and pXYZ-S tokens convert to pXYZ-T tokens on a 1:1 basis.

All pXYZ-T tokens become a transferable token at this point and all parties can freely trade (all tokens are liquid).

This approach would require regulatory clarity as the mentioned profit distributions may render some of the aforementioned tokens as securities according to some regulatory entities.

Strengths

Creates a true preference of stake and establishes a senior right.

Weaknesses

These different classes of token are illiquid (non-transferable).

Requires a value capture mechanism and can cause challenges for value accretion towards the utility token.

Creates a more complex tokenomics structure.

Makes it difficult to implement vesting structures.

Requires regulatory clarifications / compliance.

We note that it is not always preferable for an early stage company to distribute proceeds, as it can curtail growth. We can introduce a “staking” mechanism where after the cliff on the cashflow token expires, the investor has the option to redeem pro rata of the treasury or keep it in the treasury (and take risk), and be paid for the contribution in the future (loan, rewards, etc). This essentially guarantees a minimum ROI for early investors, but also gives them the opportunity to re-invest in the growth of the company. Whereas, traditionally, the investors typically do not have dividends rights preferences, and instead this is left to the company to decide. The distinguishing feature here is that these windfall mechanics are enshrined in the project / company / protocol from inception and are not subject to the discretion of the executives of the company later.

Build with us

We envision a product or two built around the aforementioned ideas. Please contact us if you are interested in contributing.

Per usual: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.”

Acknowledgements

This work was motivated by an observed scarcity of thought and reason in certain corners of the crypto venture market. We hope that this work is useful and instigates an avenue of thought. We are indebted to all reviewers for their comments and feedback, particularly Akash Nath, Tom Meister, Jin Kang, Ron Palmeri, and @_kabat_.